Our news is free on LAist. To make sure you get our coverage: Sign up for our daily newsletters. To support our non-profit public service journalism: Donate Now.

"This is the first time I've been inside your house in over a year," I say to my mother as I place the grocery bags on her kitchen table. She stops and stares at me. "De veras es un año?" she asks. ("Has it really been a year?") It was hard to believe but more than a year had passed since Ma and I had stood within six feet of each other.

We were together because I had asked her if we could make capirotada, a bread pudding-like dessert commonly prepared during Lent in many Mexican Catholic homes. The dish is made by frying sliced bread, soaking it in piloncillo syrup then topping it with cheese and dried fruit. It's a study in contrasts. The sweetness of the syrup vs. the saltiness of the cheese, the warm liquid vs. the cool toppings, the crunchiness of the bread vs. its soft, doughy interior.

Like many Mexican kids, I grew up eating capirotada — and not just during Lent. In my house, we ate it whenever Ma had a craving. I loved it but I also took it for granted. It wasn't until I was an adult that I realized my mother's recipe was also a marriage of tradition and innovation, a fusion of her Mexican childhood with her life in the United States.

Like many immigrants, Ma has never truly felt American. "Hago cosas como los americanos, pero que yo diga que me siento 100% americana, no," she says. ("I do things like Americans, but for me to say that I feel 100% American, no.") I think her capirotada recipe suggests that she's more American than she knows.

MY MA'S MEXICAN ROOTS

Ma was born and raised in Quiroga, Michoacán, a town known for its carnitas, its hand-painted pottery and its carved wood decorations. She left school after second grade and found herself working different jobs: tortilla delivery girl, decorator of tourist souvenirs, assistant at a pharmacy run by a family friend. When she wasn't working, she was cooking with her mother, my grandma Trinidad, who we all call Mama Kikis.

Every year during Lent, Mama Kikis made capirotada. Unlike most recipes that call for dried-out bolillo, in Quiroga they use a special bread. Pan tostado para capirotada (toasted bread for capirotada), made only during Lent, further cements the dish as an ephemeral treat. Good luck finding the bread after Easter.

I called my tía Socorro in Quiroga and she confirmed that all the bakeries in town make it during Lent. Most only offer it on Fridays but one bakery sells it all week long. As far as she knows, pan tostado para capirotada isn't made in any of the neighboring towns. If you want this bread, you have to come to Quiroga.

My tía describes the bread as having the hue of café con leche. It's about the size and shape of a large chancla and just as thick. Her neighbor, a baker, says the dough is sweetened with a bit of sugar and cinnamon, but not too much. The bread is baked twice. First, small balls of dough are placed inside a hot oven where they are left inside just long enough to sanconchar (partially bake). This is when they take their chancla shape. The bread is taken out and the oven is left to cool but not completely. Then, it's returned to the oven on low heat for 5 to 7 minutes so it can toast. (If the heat is too high, it'll burn.)

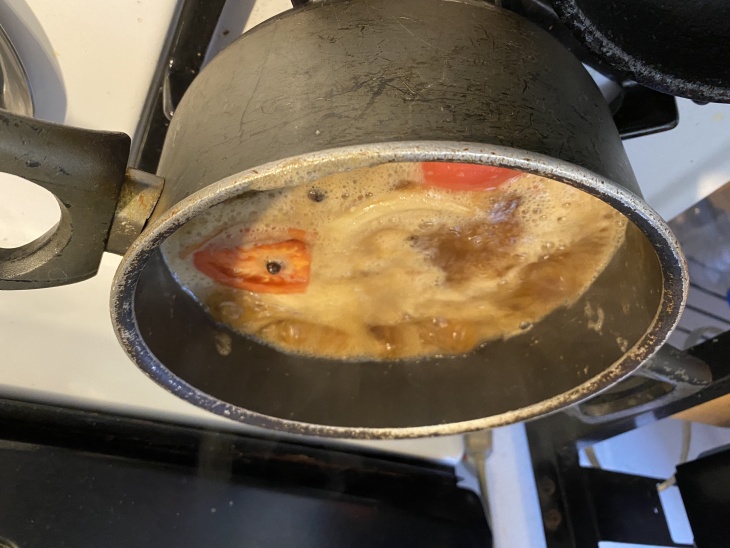

Mama Kikis relied on pan tostado para capirotada for her comparatively minimalist version of the dish. While other recipes call for a number of toppings — bananas, apples, plums, coconut — she used only dry cheese and raisins. She boiled peppercorns, allspice, cloves, onions, tomatoes and piloncillo in water to make the syrup. Once that was done, Mama Kikis fried the bread in oil, drained it and arranged it on a plate. Then she poured the syrup over the bread and added the cheese and raisins.

Although my mother had learned to make capirotada from Mama Kikis, she had only made it this way on her own one time. Because she could not uniformly glaze the bread, some sections were soaked while others remained dry. Ma discovered that if she dipped the bread in the syrup immediately after frying, the pieces were uniformly saturated. She learned early on not to get upset when things didn't turn out as expected. Instead, she found a workaround. That mindset would serve her well when she immigrated to the United States.

FINDING THE RIGHT INGREDIENTS IN LA

My parents arrived in Los Angeles in 1985 during Lent. Ma longed to make capirotada but she couldn't find the right bread. At that time, she had trouble finding a good Mexican bakery in South L.A., let alone one that served anything resembling Quiroga's pan tostado. She settled for sliced bolillo, took it home and started preparing the capirotada but the bread disintegrated when dipped it in syrup. She was livid. She tried bolillo from another bakery. Same result. In her frustration and stubbornness, she vowed never to make capirotada again.

My parents had only planned to stay in the U.S. for a little while, just long enough to earn the money to build a house back in Mexico. But after five years, they were nowhere near that goal and I had to start school, so they resolved our legal status and we stayed here. By then, Ma had grown accustomed to American ingredients and had started incorporating them into our meals.

One of the first things she used were store-bought biscuits, the kind that pop out of the cardboard cylinder when you peel off the label. She liked how easy they were to make. One day, she bit into a biscuit that had grown stale. Not wanting to throw away the batch, she thought about dunking them in coffee or milk. Then she had a Eureka moment, "What if I make these into capirotada?!"

She sliced the biscuits in half, fried them in oil and dipped them into the syrup. They held up. They didn't taste like Quiroga's pan tostado but they hadn't disintegrated into a pile of mush. From that day forward, Ma never made capirotada with any other bread. Her willingness to experiment with different ingredients — these days, an enterprising influencer would call it a "kitchen hack" and post a clout-generating Tik Tok about it — reshaped her outlook on life in her new country.

She had been forced to improvise, to make her favorite meals with whatever ingredients she could scrape together in her new homeland. The results didn't taste like they would have back at home but they tasted good — sometimes better — and the freedom to add a personal twist to traditional recipes was priceless. Like centuries of immigrants before her, she was practicing fusion cuisine long before posh restaurants and pedigreed chefs made it a trend.

MAKING CAPIROTADA IN 2021

Cooking with Ma has always been difficult. She doesn't write down recipes or use any officially recognized system of measurement. Taza means coffee cup. Cucharada means whatever spoon is nearby. It's a lot of tanteale — "You'll know if you've used enough."

When we made capirotada this year, she had baked and sliced the biscuits the day before. So when I arrived at her house, she started boiling the ingredients to make the syrup while I grated the cotija. "Lleva tomate la miel?" she asked. ("Does tomato go in the syrup?") "Shouldn't you know?" I replied. "It's your recipe."

This is why I've started to write these things down. After a brief call to my other aunt, Maria, Ma plopped a tomato into the saucepan with the other ingredients and brought it to a boil.

While it was simmering, she heated the oil and plopped the biscuits into the pan, frying them for a few seconds on each side then dunking them in syrup. I only had to ruin three biscuit halves before I found my rhythm.

Ma cautioned me to pay attention to the order in which I was frying and dipping them. That way, I could make sure to remove them from the syrup in the same order, before they got soggy.

We fried, dipped and arranged the biscuits in the baking dish, then layered them with cheese and raisins. As we finished, my mom grabbed a biscuit and popped it in her mouth. I did the same. I felt like Anton Ego in Ratatouille. A montage of Ma lovingly preparing capirotada in the kitchen of our small Huntington Park apartment flashed through my mind as I savored the sweet, salty, syrupy goodness. I smiled as I reflected on Ma's ingenuity.

Here she was, an immigrant who had always felt like a bit of an outsider in her adopted homeland but thriving — using everything at her disposal to recreate the culinary pleasures of her childhood for her own family. It doesn't get any more American than that.

Recipe: Ma's Non-Traditional Traditional Capirotada

Like most immigrants, my mother cooks from memory and doesn't use traditional measurements. The recipe below offers a close estimation of her amounts. It's a good idea to bake the biscuits ahead of time, usually the day before, so you can let them cool before you slice them.

Prep Time: 15 mins

Cook Time: 45 mins

Servings: 4-6

INGREDIENTS

3 cans refrigerated biscuit dough (Ma prefers the small buttermilk biscuits that come 10 to a can but you can use other biscuits as long as they're not sweetened)

6 cloves

6 black peppercorns

6 allspice berries

3 6-ounce piloncillo cones

1 cinnamon stick

1/8 white onion (my mom calls this a "piquito")

1 small tomato, cut in half

3 cups water (my mom uses a regular coffee mug to measure this)

8 ounces cotija cheese, grated or crumbled

1 cup raisins

1/2 - 2/3 cup vegetable oil

DIRECTIONS

- Bake the biscuits ahead of time. The day before is a good idea. Allow them to cool to the touch. Slice them in half and set aside

- In a small saucepan, combine the cloves, allspice, peppercorns, tomato, onion, cinnamon, piloncillo and water. (Ma recommends breaking the piloncillo into smaller pieces so it dissolves faster.)

- Bring to a boil, stir and cook for about 5 mins, then reduce the heat to let the syrup simmer.

- While the syrup simmers, heat the vegetable oil in a frying pan over medium heat. Once the oil is hot, add the biscuit halves to the oil and fry them for approximately 15-20 seconds, or until lightly toasted, on each side. Add more oil if necessary.

- Let the excess oil drain from the biscuits. Immediately place them in the simmering syrup. Using tongs, flip the biscuits so they're coated on both sides with syrup. Don't keep them in the syrup for more than 15 seconds, so they don't absorb too much liquid and fall apart. Drain the excess syrup and put the biscuit in your serving dish.

- Layer the bottom of the dish with the biscuit halves. Sprinkle the cotija on top, followed by raisins. Repeat the biscuit/cotija/raisins process, creating layers until you've used all your biscuits.

- Strain the leftover syrup and save it to make more batches of capirotada. (Ma says it will keep for one month, but it never lasts more than a week in my house. We use it to sweeten coffee.)

SERVING

When Ma serves it, she doesn't try to get a slice with all the layers. (It's not lasagna.) Instead, she picks off the top layer of biscuits and serves them, working her way down through the layers. The bottom layer will be the sweetest.

WE LOVE TO ANSWER YOUR QUESTIONS

"bread" - Google News

March 24, 2021 at 09:00PM

https://ift.tt/2P5A8q7

Capirotada, The Easter Bread Pudding That Sweetened My Ma's Relationship With The United States - LAist

"bread" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2pGzbrj

https://ift.tt/2Wle22m

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Capirotada, The Easter Bread Pudding That Sweetened My Ma's Relationship With The United States - LAist"

Post a Comment