“In such an ugly time, the true protest is beauty.” –folksinger Phil Ochs, 1968

I am running for Vice President of the United States on the Bread & Roses Party ticket (www.breadandroses.us). Along with presidential candidate Jerome Segal, a University of Maryland philosopher and public policy professor, I’ll be on the ballot in Maryland, Vermont and perhaps a few other “safe” states, where our candidacy cannot possibly result in a victory for President Trump. We are not “spoilers,” and would be delighted if the Democratic Party took on a few of our ideas—no credit expected.

Bread and Roses Party logo

With its broad quality of life focus, its emphasis on beauty and cultural transformation, Bread & Roses is unique in American politics. We support many of the progressive ideas advanced by senators Sanders and Warren, including universal healthcare, an increased minimum wage, progressive taxation, and a Green New Deal. But the most distinct feature of our political outlook, is “Roses,” a focus on beauty, nature, creativity, meaning, and “the time to do those things in life that are most important.”

Along those lines, we are calling for the immediate adoption of a 30- or 32-hour workweek, not only to restore jobs lost to COVID-19, but also to improve the health and happiness of American workers. And while we support free public education through college, we are equally concerned with its content, advocating a focus on humanities, arts and critical thinking skills rather than on job training.

In American politics we tend to talk about inequality almost solely in economic and monetary terms. We speak about fairness mostly in relation to redistributive taxation or higher minimum wages. Even progressive policy makers gauge our success as a society through growth of the Gross Domestic Product, a sum of the market value of the goods and services we produce in a given year.

Young Lake Beach in Yosemite

But GDP is a strange measure of well-being: housework, or a walk in the woods, or a good talk with a friend count for nothing because they do not directly produce income, though they contribute greatly to our satisfaction. Cleaning up oil spills or treating cancer are expensive and therefore add considerably to GDP but are, at least in part, efforts to remediate what has gone wrong with earlier growth. Indeed, as one economist (Bartolini, 2010) has argued, a faster-growing GDP may be more indicative of dissatisfaction than happiness. It may be more a measure of economic inefficiency or what Herman Daly calls “uneconomic growth.”

Rapid growth often comes with stressful increases in work, loss of time for relationships and damage to our natural commons. To compensate, the wealthier among us take quick vacations to pristine tropical beaches or buy the products we think might win us friends. GDP goes up faster but so does the cost to life satisfaction and sustainability.

But what if our politics were different—as they once were–centered less on the fight over income and more on the public provision of non-material satisfactions? We all need material products—housing, food, etc.—to live but we tend to neglect the fact that most of our needs are less directly material—our safety needs require the conditions for good health (not simply health care); our belongingness needs require time and places to come together; our esteem needs require the competence that education and apprenticeships can provide, and our self-actualizing needs require the time, freedom and venues to express our creativity. Maslow (1970) also suggests that we have unmet intrinsic aesthetic and cognitive needs.

Bread and Roses

In 1910, the suffrage leader, Helen Todd, spoke of our material needs as “bread” and the non- or less-material as “roses.” Votes for women, she told an Illinois audience, would “go toward helping forward the time when life’s Bread, which is home, shelter and security, and the Roses of life—music, education, nature and books—shall be the heritage of every child that is born in the country…” Todd’s phrase “bread and roses” became the title of a famous poem a year later: “Small art and love and beauty, their drudging spirits knew,” wrote James Oppenheim about the marching women in a New York textile strike. “Yes, it is bread we fight for but we fight for roses, too!” In 1912, other striking women, in Lawrence, Massachusetts, reportedly carried banners reading: WE WANT BREAD…AND ROSES, TOO!

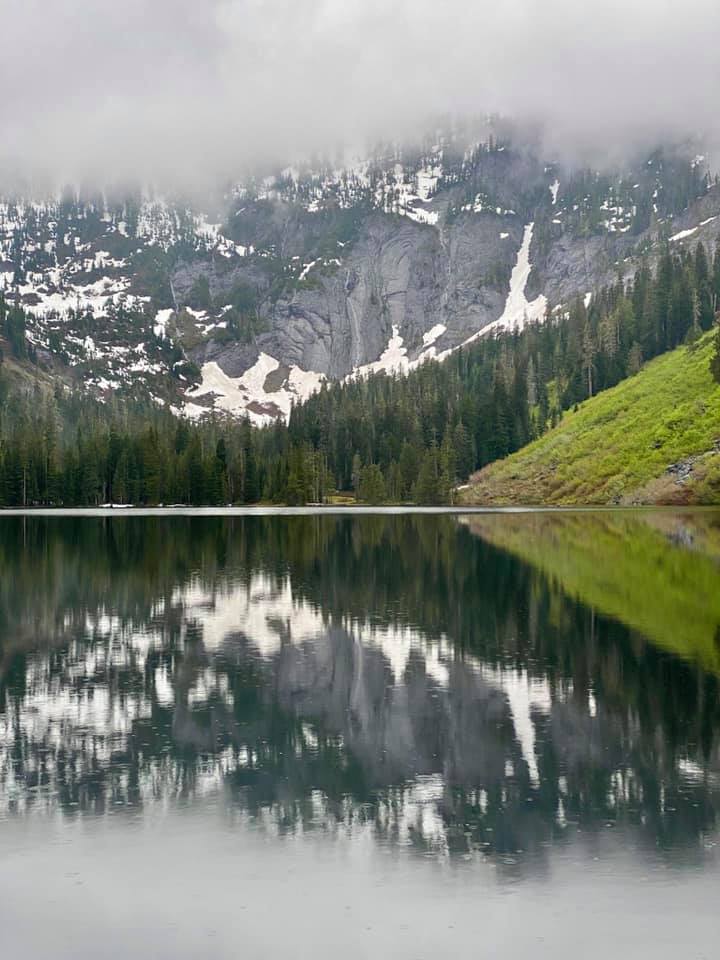

Marten Lake reflection, WA Cascades

The City Beautiful

At the same time, a more middle-class movement, City Beautiful, sought to bring parks and green spaces as well as lovely gathering places, to American cities, as had Frederick Law Olmsted half a century earlier (Wilson, 1989). There seemed to be a sense at all social levels that much of what mattered in life was not manufactured and sold, and was best appreciated with others, in public spaces. Olmsted believed that no city dweller should live more than a short walk from a park. His New York Central Park was a vast democratic space open to all. Poor and working-class women considered it a godsend where they could escape the horrors of factories and tenements.

While we often believe we are more open about our emotions these days, an NPR story revealed that a hundred years ago, people were much more likely to wear their hearts on their sleeves and speak of things like love and beauty. We are more guarded now, more ironic, more likely—since post-modernism suggested that concepts like beauty were simply social constructs—to avoid the term in policy dialogue. Our language may be poorer as a result. We choose more measured words; for example, happiness becomes well-being, and nature’s gifts are “ecosystem services.” We speak of sustainability, but such language does not compel or move most of us.

Nature’s beauty seems to be a more universal taste than the post-modernists believe. Around the world people tend to flock to particular places considered beautiful by almost everyone. People of every culture find our national parks, or our public gardens, beautiful. By contrast, in no culture do people revere or flock to garbage dumps or polluted rivers unless poverty leaves them no choice. “We all know what ugly is,” President Lyndon Johnson once remarked.

Everybody needs beauty

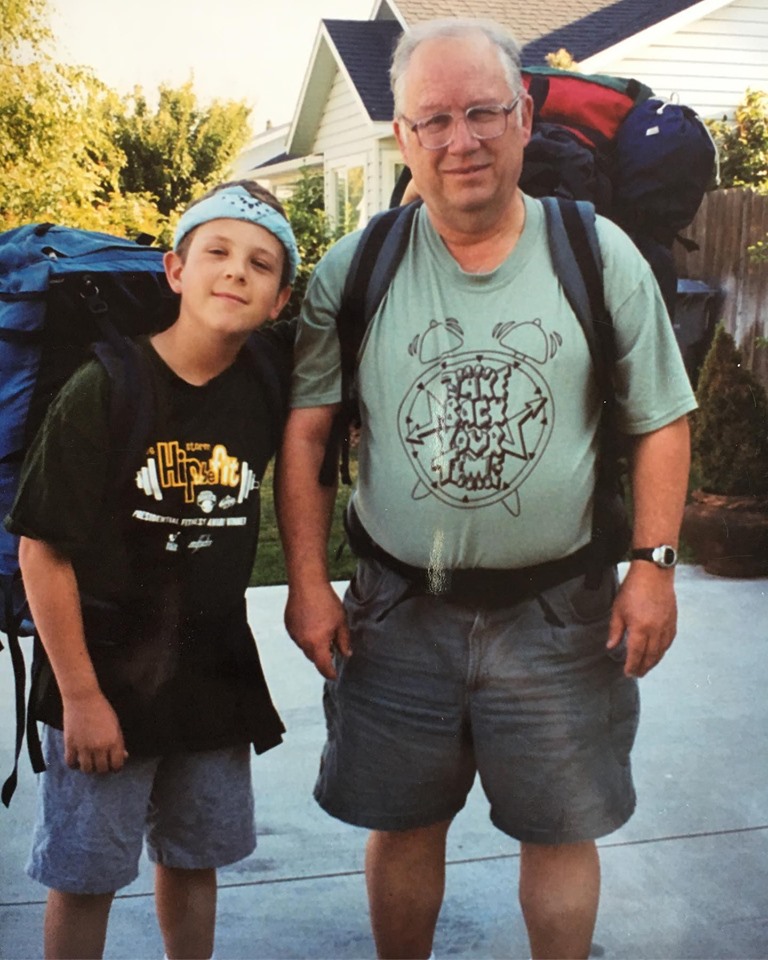

My father introduced me to backpacking when I was about ten. I enjoyed the camaraderie—with him, and later with many friends—and the healthy exercise, physical challenges and sense of freedom, all the things that leisure time can offer us. But it was the sheer beauty of nature—snowy peaks, wildflowers, deer in the meadows, sparkling streams, forest shade, reflections on still lakes at dawn—that made me, and so many others, committed environmentalists wishing to protect wilderness and expand access to parks. It was awe and wonder that hooked me forever.

My son and I leaving on a backpacking trip, 2005

Can beauty save the world?

John Muir understood that a rising material standard of living wasn’t enough. “Everyone needs beauty as well as bread,” he proclaimed.

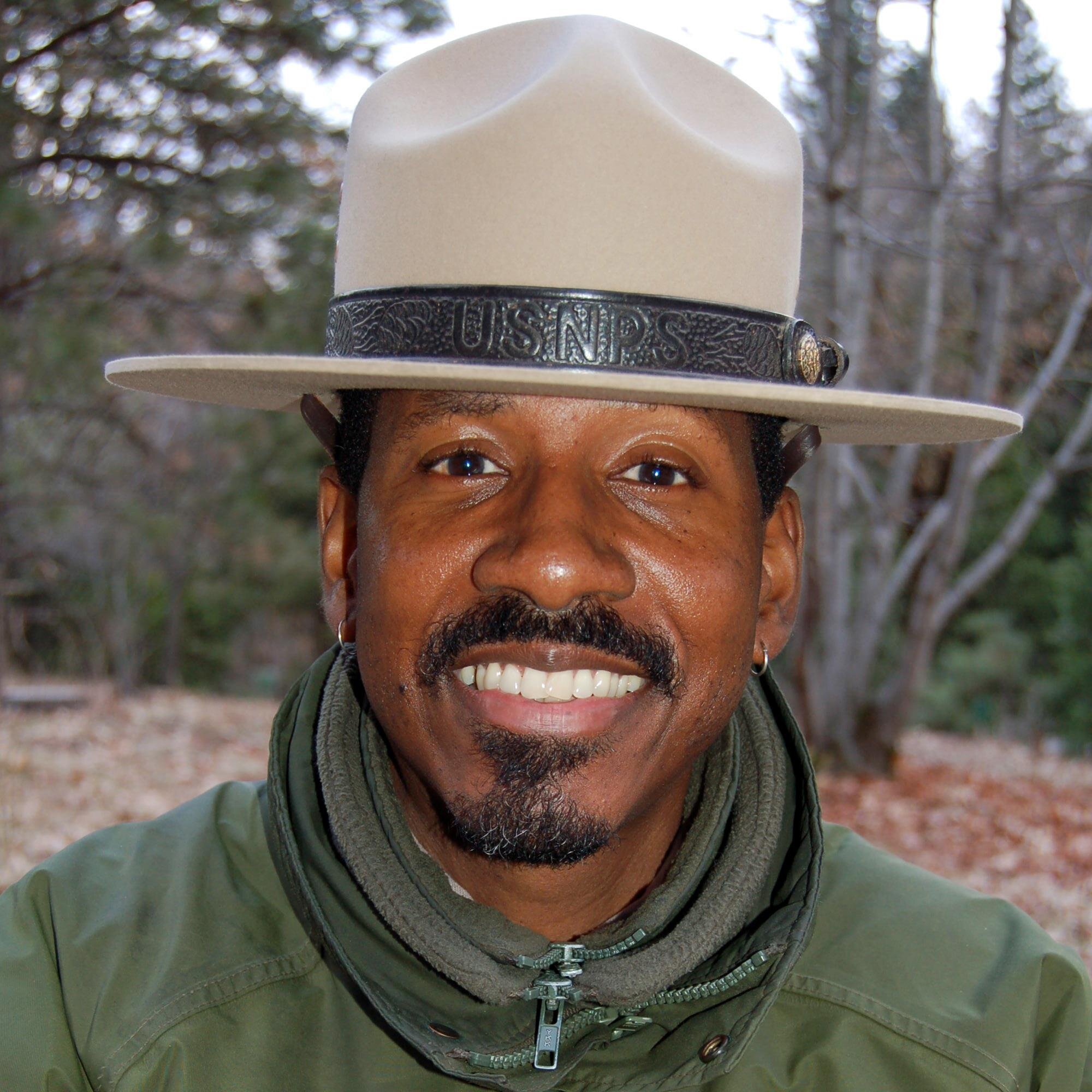

“The underserved children in America suffer from what John Muir called ‘beauty hunger’, an innate spiritual, psychological, and physical craving for the sublime, the transcendent, that cannot be fully satisfied by any human craft or invention,” says African American park ranger Shelton Johnson, referring to the children of color he hopes to see more of in Yosemite, where he has served for 25 years.

“Our kids hunger for something they’ve never tasted, a soul food that cannot be found in any city or town,” Johnson adds. “In our national parks, our children discover what was lost. By breathing deep in a forest, they can truly experience respiration. By watching the light of mountains, they can fully experience sight. By listening to birds waking the world at dawn they can begin to comprehend the miracle of sound. Only when they touch the earth will they feel the depth of their own nature. This is how they become human beings. This is how we save the world.”

Ranger Shelton Johnson

Rue Mapp, the founder of Outdoor Afro, agrees. “I had the epiphany,” she told me,” that African Americans have always known what we could do, and that was to lay our burdens down by the riverside. And that was the moment I understood nature as a healer. And we need that now more than ever. You know at a time when we are so divided, we can turn to nature as a break from the ‘isms’. You know the trees don’t know what color you are. The birds don’t know how much money you have in your account.”

Dostoevsky proclaimed that beauty would save the world. So did Solzhenitsyn. “Beauty Will Save the World,” was the title of his 1970 Nobel lecture. Dorothy Day declared that “The world will be saved by beauty,” and Doug Tompkins, co-founder of the giant North Face and Esprit clothing companies made a wager: “If anything can save the world,” he said, “I’d put my money on beauty.” Yet the poet Yevtushenko added a caution: “But who will save beauty?” he worried. It’s a fair question at a time when ecosystems are being destroyed at faster rates than ever and the UN estimates that a million plant and animal species face extinction as a result of climate change and habitat destruction.

And Beauty for All

Along with the Green New Deal, Bread & Roses advocates a “Beauty New Deal.” With others, I started the And Beauty for All campaign to call attention to the power of beauty to both save and restore our fragile ecosystems and bring Americans (and others) together for a common goal. Such an effort seems to me especially relevant for those who are concerned with both the environment and social justice. Among the aspects of our presidential campaign is advocacy of more parks and open space in our cities, especially in lower-income and marginalized neighborhoods.

Forest Light, WA Cascades

In this sense, we draw on the groundbreaking work of Bogota, Colombia’s mayor Enrique Penalosa (Montgomery, 2012). More than two decades ago, when Penalosa was first mayor (he was re-elected recently, after many years in the United States), he sought to reduce the gap between rich and poor in a city plagued with both poverty and violence. Penalosa observed that one aspect of poverty was a feeling that no one cared about their conditions, which led the poor to apathy. So instead of immediately working to boost incomes in poor areas, he built hundreds of parks and libraries, provided fast rapid transit to better jobs and banned automobiles from parts of the city. His efforts energized the poor and led to a happier, healthier, safer and more just Bogota where there is a much greater sense of community, exemplified by the mass public sharing of streets by people for much of the day on Sunday mornings, when auto travel is banned.

Satisfied cities

Beauty, suggests Harvard philosopher Elaine Scarry, is not a distraction from justice. Indeed, it makes people kinder, more tolerant, more accepting of others and more committed to fairness and cooperation. It is also an essential aspect of satisfied cities. A recent Gallup study (supported by the Knight Foundation, found that in all 26 cities (quite varied in their demography) with Knight-Ridder newspapers, three elements (among nearly a dozen suggested by the survey) stood at the top in determining residents’ sense of attachment to their communities. Gallup described them as:

- Social offerings — Places for people to meet each other and the feeling that people in the community care about each other.

- Openness — How welcoming the community is to different types of people, including families with young children, minorities, and talented college graduates, and

- Aesthetics — The physical beauty of the community including the availability of parks and green spaces.

Good schools came in fourth. Safety and incomes were well down the list. And the survey found the same top three in every city studied. The fight for beauty, as it is called in the United Kingdom (Reynolds, 2016), is a win-win proposition that can enhance both justice and the environment and reduce political polarization, as I have found recently in conversations with self-described conservatives as well as liberals. Both rank access to nature high on their list of amenities and understand its importance for health (Williams, 2017).

Sparks Lake, OR

The Green New Deal

More than half a century ago, Lady Bird Johnson, with support from her husband, the president, and Interior Secretary Stuart Udall, launched a great beautification and environmental protection campaign for America. It was wildly popular across political lines and received mostly bi-partisan support in Congress. It included beautification of cities, beginning with grants to poor neighborhoods (part of President Johnson’s demand that beauty be a right of all Americans), restoration of damaged ecosystems, bans on billboards and some junkyards, and creation of many new national parks and wilderness areas.

Now, we have another opportunity to beautify America while challenging economic injustice and pulling back from the climate-change disaster. The language of beauty for all can help move the proposed Green New Deal forward and catalyze conversations across the country. Young people will be most affected by climate change and they have been most vocal about confronting it with actions such as the Student Climate Strike and the Sunrise Movement. They can start to make a difference immediately in their own schools. Vast swaths of school properties are now covered in asphalt, for parking lots and even recess sports. These can be removed and planted with trees and school gardens. They can do their part to beautify communities and to sequester carbon as well. And they will provide productive and healthy learning experiences for children, many of whom will be needed to tend the smaller, more labor-intensive and sustainable farms that must be part of our future.

Stewart Udall and Lady Bird Johnson

Different language for sustainability and justice

The old word “beauty” speaks to our hearts as more academic or bureaucratic terms cannot. I am especially persuaded by the power of the word to cross lines of political polarization. I believe deeply in “environmental justice,” but for those on the Right such language tags the speaker as being a zealot of the Left and may stop conversation before it starts. Instead, I have come to use the phrase “and beauty for all” to convey the same message about stewardship and fairness. Though there are many exceptions—a golf course in a desert showered with chemicals and diverted water, for example—beautiful landscapes are often healthy ecosystems. “A thing is right,” ecologist Aldo Leopold observed, “when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” Integrity, stability, beauty—such terms are more likely to foster dialogue than our newer language. As, I believe, is the concept of Bread and Roses!

Lake Annette reflection, WA Cascades

Cited works:

Bartolini, Stefano, Manifesto per la Felicita, Rome, Donzelli, 2010

De Graaf, John, “The Promise of the Green New Deal,” Resilience, March 28, 2019

Maslow, Abraham, Motivation and Personality, New York, Harper & Row, 1970

Montgomery, Charles, Happy City, NY Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2012

Reynolds, Fiona, The Fight for Beauty, London, One World Publishers, 2016

Scarry, Elaine, On Beauty and Being Just, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University, 2001

Teale, Edwin Way, The Wilderness World of John Muir, Boston and NY, Mariner Books, 2001

Todd, Helen, “Getting Out the Vote: An Account Of a Week’s Automobile Campaign by Women Suffragists” NY, The American Magazine, September 1911

Williams, Florence, The Nature Fix, New York, Norton, 2017

Wilson, William, The City Beautiful Movement, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins, 1989

"bread" - Google News

June 17, 2020 at 05:16PM

https://ift.tt/3d5oRMh

Campaigning for Bread and Roses - Resilience

"bread" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2pGzbrj

https://ift.tt/2Wle22m

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Campaigning for Bread and Roses - Resilience"

Post a Comment