A total of 57 qualitative interviews were conducted between January 2017 and June 2018. Interviews lasted 80 ± 34 min (range 30–162 min). The mean age of the sample was 55 ± 10 years (range, 22–75 years). Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Qualitative phase

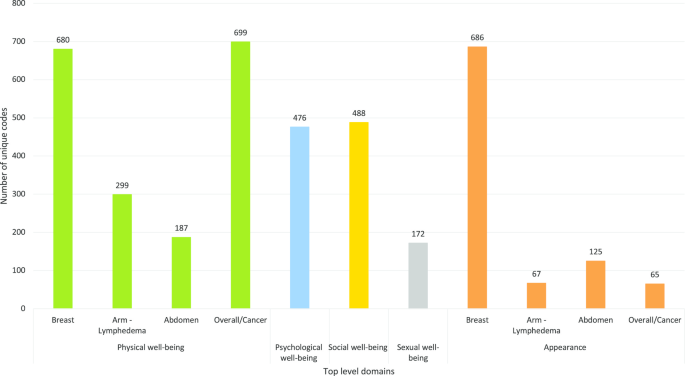

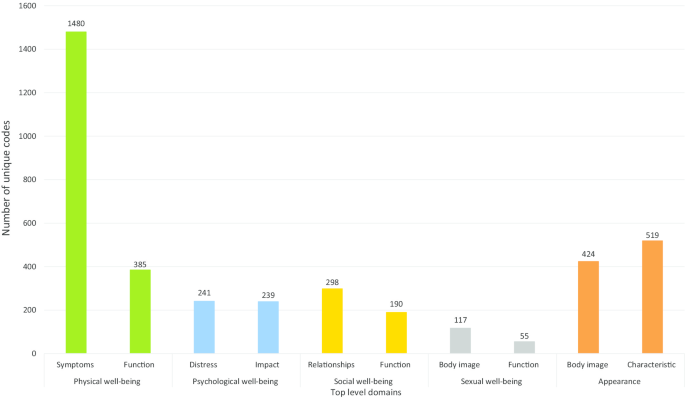

The BREAST-Q Utility conceptual framework was developed from 3948 unique codes. Five top-level domains were identified: physical, psychological, social, and sexual well-being and appearance (Fig. 2). Figure 3 highlights the subdomains. The domains, sub-domains, and themes (or dimensions) are described in detail below.

Health-related quality of life

Physical well-being

This domain was used to capture symptoms and mobility-related issues specific to breast cancer surgery and the (neo)adjuvant treatments.

Physical symptoms

Fatigue

Breast cancer treatment-related fatigue was the most disabling symptom experienced by women actively receiving treatment or in survivorship. Women described the experience of fatigue as “tired”, “wiped out”, “lethargic”, “depleted of energy”, “drained”, and “exhausted”. Women also equated the feeling of fatigue with feeling physically weak or unwell. Frequent napping during the day and unrestful sleep at night were common complaints: “I had to have an afternoon nap during chemotherapy” and “I felt lousy in the night”.

Feeling tired interfered with women’s ability to do daily activities (e.g., “took longer), caring for self or dependents, participation in hobbies or social activities (“I missed church picnic as I felt really lousy”), and work (“I could not go back to work due to tiredness”), resulting in substantial distress. Women reported reduced interest in sexual activities (“too tired to have sex”) as a result of fatigue.

Pain and discomfort

Women who were undergoing treatment(s) commonly reported pain or discomfort that varied by type (dull, sharp, ache, shooting), intensity (mild, moderate, severe), frequency (constant, intermittent), and location. Pain due to breast cancer surgery was described as “dull ache”, “discomfort”, or occasionally as “sharp” or “electric”, and was worsened due to sleeping in certain positions (e.g., side-lying or prone) and movement of the arm(s). Women reported pain in the breast area, shoulder or arm, and due to wound care in the immediate postoperative period. For most women, pain interfered with sleep (“pain wakes me up at night”, “I cry out in pain in sleep”) and restricted their ability to participate in daily activities. Participants with abdomen-based reconstruction described feeling “discomfort”, “bloated”, or “tightness” in the abdomen area that was aggravated by sudden or sharp movements (e.g., coughing, straining for bowel movements).

Pain due to systemic therapy was described as “constant”, “deep”, “excruciating”, “sore everywhere”, “arthritic”, with or without morning stiffness, and was frequently experienced in lower extremity joints. This type of pain was often described as “debilitating”, and impacted sleep, mobility (e.g., walking, stairs), bed or chair transfers, and daily activities.

Breast sensation

Most women reported a lack of feeling (“numbness”) in their breast area (including axilla and in/around scar) for months following breast surgery. Many women reported their breast(s) intermittently feeling “hard”, “full”, “heavy”, “cooler than rest of the body”, and feeling “electric shocks”, “lightening”, or “firework-like sensations”. A small number of women experienced phantom symptoms on the surgical side, including “deep itch”, or “feeling of milk coming down”.

Peripheral neuropathy

Some participants who underwent systemic therapy experienced peripheral. The feelings of “numbness”, “tingling”, “pain”, or “pins and needles” was reported. Neuropathy in the hands was reported to interfere with fine motor tasks, such as holding a pen, buttoning a shirt, screwing or unscrewing jars, sewing, lifting a cup, or carrying or lifting grocery bags. Neuropathy in the feet caused pain or loss of balance and interfered with walking and physical activity.

Other symptoms

Less frequently described symptoms included altered taste, loss of appetite, nausea or vomiting, mouth sores, hot flashes, dry eyes, weight gain or loss, headaches, feeling lightheaded or dizzy, dyspnea, tachycardia, vaginal dryness or itching, and frequent urination. Some women described difficulty remembering things, and issues with recall, focus, or problem solving (“brain fog” or “chemo-brain”) during and for months following systemic therapy.

Physical functioning

Mobility and daily activities

Some women reported difficulty with moving or lifting the arm on the surgical side, especially in the immediate postoperative period. The reduced arm mobility interfered with personal hygiene (bathing, washing hair), self-care (applying makeup, styling hair, getting dressed), household chores (meal preparation, laundry), overhead activities (“I could not put stuff up in the high cupboard”), lifting objects (“I couldn’t lift or hold things for a long period”), driving, exercising, hobbies, and/or recreational activities. Women who were seeking or had undergone systemic therapies reported mobility issues due to pain and fatigue. This interfered with activities such as bed or chair transfers and doing stairs. Women with abdomen-based autologous reconstruction also reported difficulties with bed and chair transfers especially in the immediate post-operative period. Participants reported using accommodations such as hired help, bath chair, gait aids (walker, cane), and specialty shoes (for neuropathy).

Sleep

Women reported concerns with the amount and quality of sleep, including difficulties with falling asleep, staying asleep, and interrupted sleep often due to the side-effects such as nausea, hot flashes, pain, or discomfort. Suboptimal night sleep often resulted in daytime fatigue and women reported needing to nap during the day. Sleep was also affected in the post-operative period due to having to sleep in unfamiliar positions. A few women reported sleeping in a recliner chair or speciality bed during the postoperative period. Some women recovering from implant-based reconstruction felt discomfort or anxious about putting pressure on their implants in the prone position.

Psychological well-being

Emotional distress

Women described feeling anxious or worried about losing their breast(s), treatments and their side-effects, prognosis, cancer recurrence, and the impact of cancer and its treatment on their significant other and family members. Women described the off-treatment phase as particularly stressful as they no longer felt they were proactively preventing cancer recurrence (“not having chemotherapy makes me anxious”). Women reported feeling distress about new symptoms that appeared post-treatment (e.g., aches or pains) and about receiving test results.

Women described feeling angry, frustrated, disappointed, or irritated upon diagnosis. This feeling was often replaced with sadness (“depressed”, “upset”, “feel awful”, “overwhelmed”) about losing their breast(s), chemotherapy-induced alopecia, and inability to fully participate in daily activities during their treatment and the recovery period. All women with young children worried about the possibility of not experiencing life with their children. Some women reported dwelling on their diagnosis, effectiveness of the treatment(s), cancer recurrence, or late effects of treatments (e.g., cardiotoxicity).

Positive impact

A few women described their coping strategies and how they saw their diagnosis as an opportunity to restructure life, build personal connections, pursue new hobbies, or travel. Women were grateful for their support network, timely access to treatments, going into remission, and being alive (“I remember thinking I’ve lost a breast, but I haven’t lost my life”). Some women reported change in their outlook toward life and living with more gratitude and in the present.

Social well-being

This domain covered social issues in relation to the diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship phases. These codes were classified into social participation, isolation, and relationships.

Social function

Social participation

Women reported limitations in their ability to participate in their usual social roles, including caring for self and family, work, and community roles. Side-effects (e.g., pain, fatigue, neuropathy) of cancer treatments impacted women’s work-life into the recovery and survivorship phases. Some women modified their work responsibilities by asking for accommodations (“reduced the number of hours worked” or “took more breaks”) or discontinued employment (temporarily or permanently). Women also reported requiring assistance with childcare and help with household chores, resulting in an emotional or financial burden on the family.

Social isolation

Social isolation was described as necessary in the context of chemotherapy to avoid infection. Symptoms such as fatigue and body image-related issues (especially alopecia) interfered with the ability or choice to participate in social events. Treatment factors, such as the daily burden associated with radiation therapy, also prevented women from socializing with friends or family. Lack of participation in meaningful activities (work, or leisure) contributed to a sense of loneliness through the breast cancer experience.

Relationships

Provision of emotional, instrumental and informational support from others was central to women’s experience of breast cancer. Being driven to healthcare appointments, and help with housekeeping, meal preparation, and childcare was invaluable. Many women relied on visits and talking with family members to cope with their illness. Most women struggled with their new role as a dependent and worried about their partner taking on caregiving responsibilities. Given how common breast cancer is, participants leaned on relatives or friends who were diagnosed with breast cancer for information about treatments, side-effects, and remedies.

Sexual well-being

Sexual self-image

Changes in appearance due to breast cancer treatment affected women’s sexual self-image and sexual interactions. Most women reported feeling less attractive in intimate scenarios and reduced satisfaction due to pain or lack of sensation in the breast area. Some women were bothered by their partner looking at or touching their breast area and mentioned covering up during intimate scenarios.

Sexual functioning

Women who were sexually active expressed concerns due to fatigue, loss of libido, and vaginal dryness, itching or irritation, and dyspareunia, that impacted their ability to experience sexual pleasure. Women used terms such as “not as often”, “less frequent”, “not interested”, “non-existent”, or “lost intimacy” to describe their experience. Many survivors reported a persistent depressed mood or sadness and/or anxiety that lasted beyond the treatment phase secondary to fear of recurrence, impact on partner and family, and body image concerns. These factors affected some women’s ability to orgasm resulting in reduced sexual frequency. This was particularly relevant to younger women with breast cancer and single women who were seeking a partner.

Appearance

This domain captured women’s appraisal of their physical appearance. Subdomains were categorized into appearance of the breast, abdomen (autologous reconstruction using abdominal tissue), arm due to lymphedema, and overall appearance.

Breasts, breast area, and nipples

The appearance of the breast(s) or breast area before and after breast cancer surgery was the most frequently mentioned concept. Women appraised their breast area by describing the contour (“caved in,” “bulge”, “droopy”, “puckered”), symmetry (“closely matched”, “looked similar”, “one smaller than other”, or “one higher than the other”), shape (“concave”, “flat”, “hollow”, or “full”), size (“same”, “small”, or “bigger”), and ptosis (“hang”, or “droop”). Most women described the appearance of their breast in terms of how “natural” or “normal” they looked compared to before surgery and/or to other women. Women who had radiotherapy described changes to the skin of the breast area (“looks sunburnt”, “I have a permanent tan”).

Abdomen and belly button

For abdomen-based autologous reconstruction, women were bothered by a shift in the position and size of the belly button (“much larger than what I used to have”, “doesn’t look original”). The position and color of the abdomen scar were identified as issues that could be concealed with clothing. Some women were bothered by dog ears that were visible when clothed.

Arms-Lymphedema

Women with lymphedema described the appearance of their affected arm(s) in terms of the size (“bigger”), contour (“rounded”, or “full”), shape (“indented”), and color (“lighter”). Women mentioned challenges associated with concealing the arm (finding clothes that fit) and feeling self-conscious in public (“I wear long sleeves if I was going out for dinner”).

Overall appearance

All women who underwent chemotherapy experienced alopecia, and while some women were extremely bothered by alopecia, others perceived it as a temporary issue. Most women coped with alopecia by cutting their hair short prior to starting chemotherapy and by wearing a wig, scarf, baseball cap, or toque in pubic settings. Some women reported using makeup to conceal loss of eyebrows and eyelashes. A few women noted changes to their skin (“dry”, “pale”) and nails (“black”, “loss of nails”).

Quantitative phase

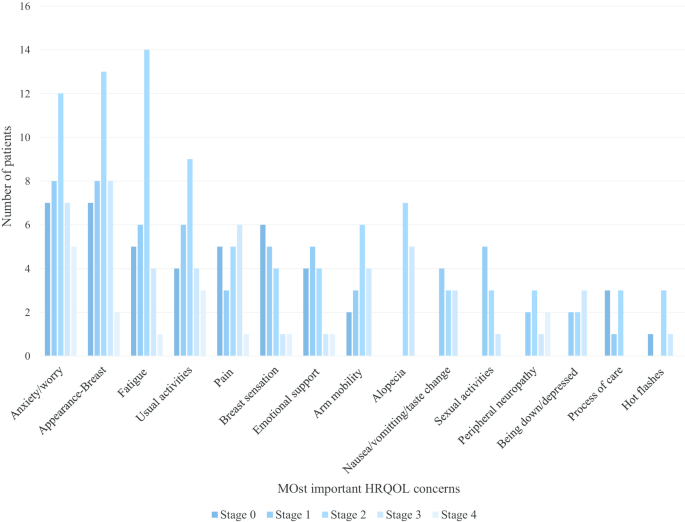

Top five HRQOL concerns: patients

The top HRQOL concerns by the stage of breast cancer are shown in Fig. 4. Overall, appearance of the breast(s), fatigue, cancer worry, impact on usual activities, and feeling anxious were the top five HRQOL concerns across all stages of breast cancer.

BREAST-Q- Item ratings: patients

Women consistently endorsed the following items to be important to their breast cancer experience across all three BREAST-Q modules: satisfaction with appearance (closely matched, feel natural, look in mirror unclothed), psychological well-being (confident, emotionally health, attractive), physical well-being (pain), sexual well-being (sexually attractive, confident sexually, sexually attractive when unclothed), and adverse effects of radiation (skin feeling dry, looking different). Women who had abdomen-based surgery endorsed difficulties sitting up, everyday activities, and discomfort in the abdomen area as the most important concerns.

Selection of domains and dimensions within domains

The findings described above were used to develop the first draft of the BREAST-Q Utility module. This version measured 9 unique dimensions (i.e., 9 items) with 4–5 response options each (Version 1). Based on the expert feedback, 3 new items were added, and the initial item measuring pain and unpleasant symptoms was split into two items. In addition, the instructions were modified to include a recall period and the wording of some of the items was modified. The revised version (Version 2) included 12 dimensions (14 items) with 4 response levels each.

Refining the BREAST-Q Utility module

Cognitive interviews were conducted from October 2018 to April 2019. Interviews lasted 60 ± 14 min. Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. Version 2 was shown to five women. Based on participant feedback, several items and the response options were revised, resulting in Version 3. This version was shown to four women and further revised resulting in Version 4. This version was developed into a REDCap survey. A total of 35 experts were invited to provide feedback out of which 27 responded (response rate, 68%). The experts included medical oncologists (n = 3), radiation oncologists (n = 3), breast surgeons (n = 15), health economics and/or outcomes researchers (n = 5), and a patient advocate. Experts were from the United States (n = 10), Canada (n = 7), the Netherlands (n = 4), Poland (n = 2) and Chile, Denmark, Italy, and United Kingdom (n = 1 each). The Utility module was revised based on the expert feedback, resulting in the field-test version of the Utility module (Version 5). Table 2 summarizes the item reduction and refinement steps.

Health state classification system

The field-test version (Version 5) of the BREAST-Q Utility module (Additional file 1) includes 10 unique dimensions: fatigue, pain, emotional distress, impact on usual activities, how the breasts match, feeling self-conscious about how breast(s) look, breast sensation, arm mobility, treatment-related unpleasant symptoms, nausea, peripheral neuropathy, and radiated skin changes. Each dimension is measured by one or two candidate items each with four or five response options. Response options for items asking about breast appearance, body image, and sensation were based on severity, while the response options for items asking about fatigue, pain and emotional distress included options to measure severity and interference with daily activities in order to test alternate ways of measuring these concepts. The final set of field-test items totalled 21.

"breast" - Google News

January 06, 2021 at 10:13PM

https://ift.tt/35hMDnr

An international mixed methods study to develop a new preference-based measure for women with breast cancer: the BREAST-Q Utility module - BMC Blogs Network

"breast" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2ImtPYC

https://ift.tt/2Wle22m

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "An international mixed methods study to develop a new preference-based measure for women with breast cancer: the BREAST-Q Utility module - BMC Blogs Network"

Post a Comment